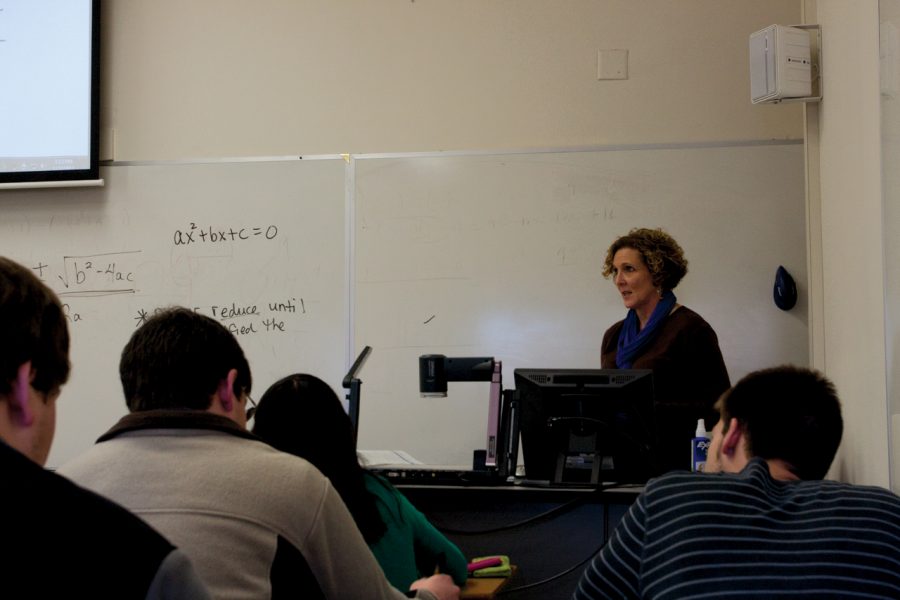

Faculty discuss ‘stereotype threat’ in math=

February 2, 2012

For years, scientists have attempted to explain why more men than women excel in higher-level math, and since 1999, it has been generally accepted that the reason was a psychological phenomenon known as “stereotype threat.”

This decade-old theory claims that poor self-esteem caused by negative outside pressures is the reason women are statistically not on par with men in mathematics.

Earlier this month, a new study was published in “General Psychology Review” entitled, “Can Stereotype Threat Explain the Gender Gap in Mathematics Performance and Achievement?” which challenges the old theory. The study claims the evidence for the stereotype threat is not sufficient and does not explain the difference in men’s and women’s achievement in math.

However, UNA’s math program has not reflected these trends in either enrollment numbers or success rates.

Dr. David Muse, chair of the Department of Mathematics, has taught almost every level of math from seventh grade to college seniors. Muse said UNA’s math classes are not lacking women at all and that he has never seen his female students excelling less than his male students.

“I think the problem goes back to elementary school and the fact that there are more female teachers than male teachers,” he said. “Boys will respond better to a female teacher and girls will respond better to a male teacher, and girls just don’t have that many male teachers to respond to.

“Generally, female teachers have a natural, unconscious disposition to respond to and encourage their male students, and vice versa.”

Associate Professor of Mathematics Dr. Cynthia Stenger said women do not lack the ability to do well in math, but that math is not as appealing to them as other fields.

“There is a lot of effort to attract women to (mathematics),” she said. “They do well but do not pursue the field. We think that women do not see the interpersonal benefits of working in that field.”

UNA’s math program does not have an unbalanced ratio of men to women, Stenger said.

“If anything, there are more women in our program who are pursuing secondary education,” she said.

Sophomore Amy Brown decided to major in math before she came to UNA.

“I’ve never seen my being a girl as an obstacle, and in my second semester, I realized that being a girl gave me an advantage because, apparently, it’s uncommon,” she said.

Freshman and math major Christian Bayens said his math classes reflect that females have a slight upper hand.

“In past math classes, the girls proved themselves to be generally better than the males,” he said. “That became the trend, and it seems to have stuck.”

While the national average may show men ahead of women mathematically, UNA’s math classes-as well as the opinions of many students and faculty in the math program-show different results.