How Kanye West’s ‘Donda’ Listening Party restored my hope for humanity

August 19, 2021

Before I tell you about “Donda,” we need to travel back in time.

The Raconteurs played at the Alabama Theater. I didn’t know at the time, but they were my final concert pre-covid. It was my boyfriend’s pick, guiltily I’ll admit I don’t love “The Racs,” but we trekked from Florence to Birmingham late in the fall semester. My boyfriend, Ethan walked with his arm around me– not to warm me from the chilly November wind, but to shield me from the hordes of men jostling us on the sidewalk.

Upon entry, we were required to lock our iPhones in bags that would unlock once the concert finished. The band’s front man, Jack White, told NBC News he wanted guests to “enjoy looking up from your gadgets for a little while and experience music and our shared love of it IN PERSON.” Which, although a nice sentiment, struck me as arrogant. The speakers were unbearably loud inside the historic theater, and I couldn’t wait for the concert to be over–especially when the performance ended with White yell-lecturing the crowd about the “myriad of poor people in Alabama” and insinuated they deserved to be impoverished because the Red state handed its nine electoral votes to Donald Trump in the 2016 election.

When White let me look at my phone, I was delighted to text my mom to tell her what a disgusting take that was.

I’m not an elitist in the slightest: I’m an avid lover of reality TV, celebrities and popular culture. Their inflated sense of self-importance leaves me unphased. But as The Raconteurs berated Alabamians while playing in their state, I was unimpressed with their egotism and lack of self-awareness.

Almost two years later, my boyfriend surprised me with tickets to the second “Donda” listening party. As an Atlanta native, Mercedes-Benz Stadium– Kayne’s newest crib– was only a MARTA ride away, and we could stay with my parents for free.

Initially, I feared this would be another Raconteurs situation, though I’d listen to Ye rap “Scoop-diddy-whoop/Whoop-di-scoop-di-poop” a million times before I chose to hear White quaver and moan about how desirable he finds red-heads. But I hadn’t been in a concert/stadium setting in 17 months so why not give it a go? “Did you hear that Kayne’s been living in the stadium to finish the album?” our friend Jack yelled over the screech of MARTA rails. “For $100,000 a day,” I added as we stood to change trains. I heard that on the radio.

Jack, who had been to the first listening party, thought “Donda” would rank in the top three of Kayne’s albums. But the listening party wasn’t just for all of us in Mercedes-Benz, Apple Music broke viewing records when they livestreamed the event.

As a casual Kayne fan, I had always imagined him as a sort of tortured, musical genius and certainly a generational defining artist. Kayne West doesn’t just make music, he creates experiences. He lives in the crossroads where music, art, poetry and commerce intersect, and his unpredictability and knack for going off-script have created unforgettable moments in popular culture: his nationally televised comments about President Bush in 2005, the “Taylor, Ima let you finish” 2009 VMAs, to his insanely quotable interview featuring input on Lady Gaga and Polaroid in 2013, to his floating stage during the Saint Pablo tour of 2016, to producing the iconic Sunday Services for “Jesus is King,” Kanye doesn’t go home: he goes big.

Our seats were near the aisle, but I was blown away with how kind and polite everyone was. Aisle seats are notoriously high traffic, but everyone smiled, said hello, compliments were exchanged on shirts, shoes and makeup looks. For all the reading I’ve done about people losing their social skills in the chrysalis of quarantine, I thought the fans at “Donda” were, respectfully, social butterflies.

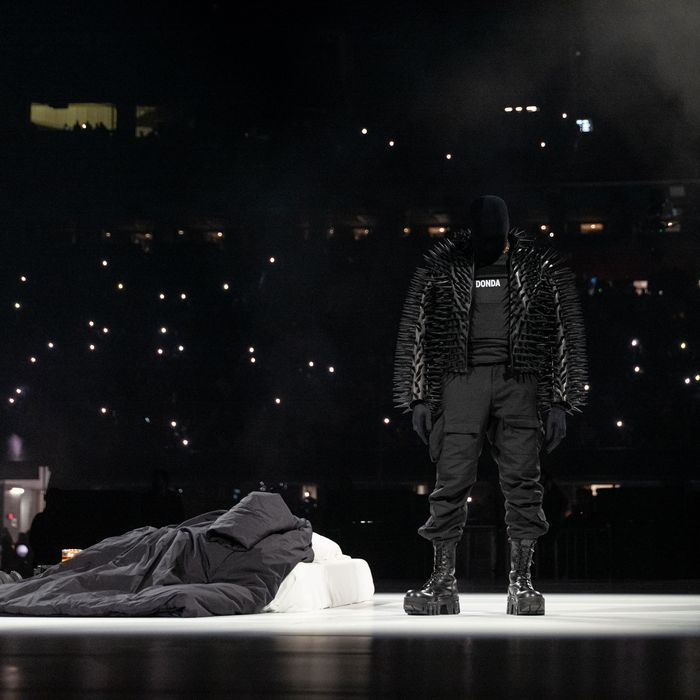

Centerfield, we saw what looked to be a set-up of Kayne’s $100,000 room in the stadium. A twin-sized mattress not unlike the blue blocks from my days in Mattielou, a burning candle, a few pairs of shoes (Yeezys probably, but it was too far to tell for sure), weights and a spiky jacket.

On Instagram, Kim Kardashian, Kayne’s ex-wife (excuse me while I grab my tissues), shared she had arrived at Mercedes-Benz in black Balenciaga to match her former husband.

Then, the lights went down. The screens turned cloudy, and Kanye ran centerfield. Music flooded the stadium with a voiceover from Kayne’s late mother, Donda West.

“I thought you said they were going to close the roof?” I asked Ethan.

“I read he asked to keep it open so his mom could watch,” he whispered.

My heart sank then bubbled up all at once when figures in black cloaks ran out from the locker rooms. They circled the Kanye’s stage as he dropped to the floor and broke into a set of push-ups.

Throughout the party, Kayne continued to act out scenes on stage while his album played in the background. The night reminded me of literature class: What was up with the hooded figures circling him? What was the significance of the spiky coat, the ski mask and the Balenciaga bullet proof vest with DONDA embroidered on the chest? I hadn’t read the book and I didn’t have the answers to the quiz. Alternatively, there may be more than one answer. Or the answer is different to everyone individually.

As the album unfolded, themes of grief and family revolved not only around the late Donda West, but also touched on his divorce. Kayne successfully wove his gospel sound into stories that undoubtably tested his faith.

As the stadium started to feel like a congregation worshiping, I started to view the people there as my neighbors instead of strangers. After the following year plus some, everyone knew everyone had struggled. Everyone could relate to the loss, fear and despair that impacted Kanye–some version or another had impacted each of us.

Yet here we were, united by music and a generational defining artist, and I felt overwhelmingly hopeful.

The crowd caught on to what we thought was the final song. Mercedes-Benz sang along, “We gonna be okay/we gonna be okay/God’s not finished/God’s not finished.” Over and over and over.

When the stadium went dark, and the crowd erupted in applause, I felt renewed. I had a sonic baptism of sorts.

We would all be okay because God is not finished.

I held that thought to my heart and believed.

Then, the lights burst towards the sky. Kanye floated, belly up and heart open, towards heaven. A spotlight illuminated his ascent to the clouds as a voice repeatedly sang “No child left behind.” Kayne and the Sunday Service Choir’s voices echoed throughout the stadium, throughout Atlanta, and throughout the country: “He’s done miracles on me.”

In that moment, everyone grabbed their phones. Everyone thought, “This is incredible. I cannot believe what I’m seeing. Kanye West is going to heaven. I must show everyone I know and love. I am so grateful to be here. To be with these people, my neighbors, my fellow Americans. We are making it. We are going to be okay.”