Female athletes face adversity

March 18, 2022

Many of history’s greatest athletes have been been women, greatness being a measure of their athletic abilities coupled with their impacts on the world.

Women, however, are societally discouraged from participating in organized sports. While women’s exclusion from activities and competitions of this nature has decreased notably over the last century, women have yet to be fully accepted into the realm of structured athletics. They are often psychologically averted to such participation, as competitive and recreational sports alike have a systemic past involving abuse and mistreatment directed at female athletes.

Sport teams, like any institutional group of citizens, employees, or students, are plagued by power imbalances and aggressions, verbal and nonverbal alike. The Women’s Sports Foundation, founded by Legendary Female Tennis player Billie Jean King, defines abuse as “the willful infliction of injury, pain, mental anguish, unreasonable confinement, intimidation or punishment through physical, verbal, emotional or sexual means.”

Regrettably, unacceptable acts of this sort are not uncommon on women’s sport teams. It is necessary this kind of behavior is identifiable; it must be addressed so that it can be eliminated. Perhaps the easiest form of abuse for authority figures to identify is that which takes place between coaches and athletes because it is characterized by an obvious difference in power.

Coaches have the ability to manipulate their players, through withholding praise and incentivizing them with time on the track, field or court. They are, moreover, in a position at which they can demean their team members, posing long-term detriments to their mental well-being. Therefore, sport team leaders should monitor the people they choose to serve as coaches and formulate written policies for them to adhere to that outline comprehensively what conduct qualifies as abuse.

Recreational sport centers, college campuses and high schools need to be equipped with trained professionals who, in the event that harassment or assault is reported, can respond with tact and push back against its perpetrator. Abuse that transpires from player to player is less instantly evident, as is habitual dysfunction amid sport leagues. Interactions players have with one another can be extremely volatile, especially on teams composed of developing girls. Furthermore, groups of maturing women have high risks of falling prey to negative self-talk and body image issues.

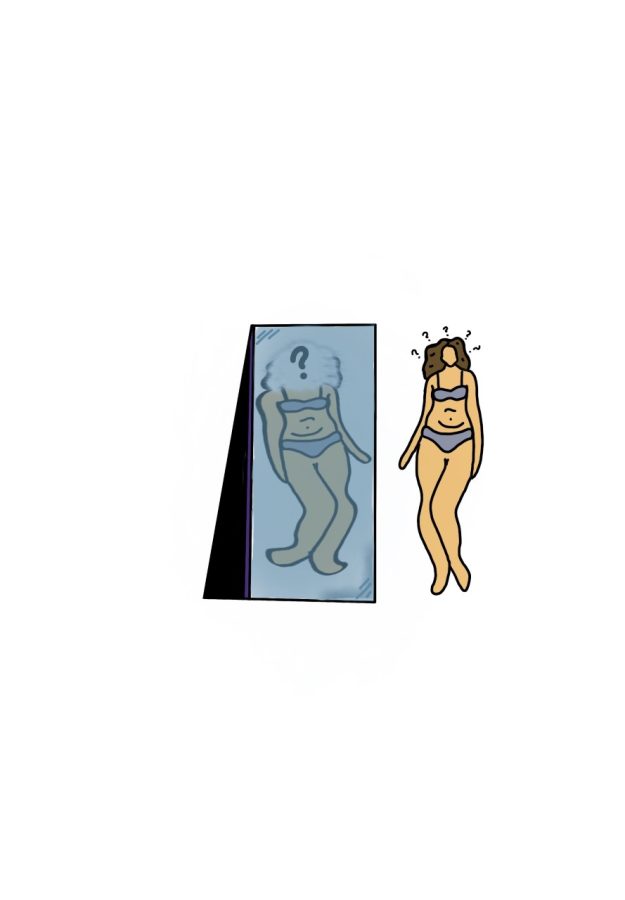

Early adolescence and young adulthood are infamously trying periods in women’s lives. When women are subjected to societal imagery denoting what is supposedly the most desirable body for a woman on a daily basis, these time frames are made markedly more difficult for them.

Female athletes struggle to come to grips with the differences in their bodies and the bodies of women seen commonly as sex symbols. Women who run, for instance, do not typically have conventionally curvy figures.

Their rigorous training regimens have them burn the bulk of the calories they consume, so they are usually slim. Having slender bodies boosts runners’ endurance. Long-distance runners in particular are, for the most part, narrow-framed, with less muscle mass than short distance runners. Their build renders them less prone to fatigue.

Eating disorders have been known to arise in the midst of athletic assemblages that are driven by feminine forces. According to Sport Science Institute, an eating disorder is a persistent disturbance of eating or an eating-related behavior that significantly impairs physical health or psychosocial functioning. It reports that eating disorders appear in female athletes with more regularity than they do in male athletes.

University of North Alabama cross country runners Mandaline Thomas and Lilly Humphries, both of whom are juniors, agree that female athletes, especially runners, have a tough time maintaining body positivity. While both women are genuinely happy to be a part of UNA’s athletic program, they each concede that they, over the course of their athletic careers, have encountered several attempted blows to their self-esteem and to the self-esteem of the women around them. “No matter what we do as cross country runners, we’ll never have your run-of-the-mill hourglass figure,” Thomas said. “We run so much.” Thomas and Humphries break down why the realization of this impossibility is disheartening for young women in the long distance running game.

“Yes, we’re small, but that doesn’t mean we have the features society expects us to have as women,” said Thomas.

Officials who manage all-woman athletic guilds have responsibilities to encourage acceptance of all body types among sportswomen and to devise measures with objectives of treating any disordered eating behaviors that exist within their teams.

Another facet of women’s sports that has proven difficult for Thomas and Humphries is the meagerness of female coaches in the industry. Despite having attended separate high schools, Thomas coming from Daphne High School on Mobile Bay and Humphries from Rouse High School in Cedar Park, Texas, both women hold that for the majority of their lives, the teams they have run on were led by men. Neither Thomas nor Humphries doubts that these men were qualified to coach their teams, but they admit it was recurrently trying to find common ground with them.

“We’ve always had male coaches,” Humphries said. “It’s harder for them to relate to their female players than it is to their male players. They know how to pace men, and they can run with men. They can do all this mileage that we can’t always do without getting hurt, and they don’t seem to realize that.” Thomas agreed with this same sentiment.

“If our coach is running with us, at the same pace as us, the conversation is created, and with that conversation comes an emotional connection,” Thomas said. “It’s hard to bond with a male coach when he doesn’t match our speed.” Evidently, it is be a great deal less feasible for female athletes to forge mutually beneficial bonds with their coaches when the teams they perform on are primarily male-led.

The unintentional shortcomings of men who work as coaches to help young women cultivate stronger foundations and heightened athletic skills does not mean they should be discredited. But they should make note of the imperfections that afflict their connections to the women playing on their teams. Considering all the obstacles standing in their way, it is admirable that so many women opt to pursue athletic accomplishments in spite of the trials they are bound to endure.