“I Didn’t Want to Call It Rape”

Three women accuse male freshman of rape in Olive Hall

Gabe Rhoden | Staff Photographer

One of the three survivors who came forward to share her story.

Content Warning: This article includes depictions of rape and sexual assault.

*Names have been changed to protect the privacy of people involved

I.

When Sarah* moved into Olive Hall in August, she looked forward to meeting new people, making new friends, going to parties and enjoying the college experience. Finishing her high school career with COVID-19 still looming wasn’t what she had planned, but at least UNA gave her a chance to start fresh.

A high school friend of Sarah’s lived down the hall.

“You’ve gotta meet my roommate,” he said. “You guys have so much in common.”

Sarah initially liked Brian* because of his connection to ROTC. Her best friend came from a military family, so it was easy for them to bond. It also didn’t hurt that he was tall, handsome and charming.

“We became close very quickly,” Sarah said. “I felt like I could trust him because we had so much in common, and he could relate to me in so many ways.”

Over a few weeks, talking turned into dating, and dating turned into spending nights together. Brian gave Sarah his hat to wear, and affectionately referred to her as “his girl.” Then, Brian started fraternity rush.

“He would go to fraternity parties, and he would drink a lot,” Sarah said. “Like, a crazy amount. You could smell alcohol on him after these fraternity parties.”

Sometimes, Brian would drink a case of Bud Light at a time. One night, while her roommate was out, Brian called Sarah. Drunkenly, he asked her to please pick him up from the fraternity house because he was too drunk to drive. Sarah agreed, but before she left, she heard a knock at her door.

It was Brian. Confused, she invited him in to investigate what was going on. He begged her to have sex.

“I will not have sex with someone who is drunk because that is not consent,” Sarah said. “He kept saying he wanted to f–k. I said ‘No. You’re drunk. You need to go to bed.’”

Sarah conceded to making out instead, but even that started to turn her off. He tasted like cheap beer.

“He started undressing me,” Sarah said. “I said ‘Brain, I don’t want to have sex. I don’t want to do this. We can make out, but I don’t want to do this.’”

It happened too quickly for Sarah to process: Brian’s pants were off. She was completely naked. He grabbed her hips and pulled her on top of him.

“Please,” Sarah said. “I really don’t want to have sex.”

Brian used one hand to choke her and the other to shove her hips down. Sarah started crying.

When it was finally over, Sarah fled to the bathroom.

“This wasn’t my first time with sexual assault, and Brian knew that,” Sarah said. “He told me he wanted to help me get over it.”

Brian called from her room. “What’s wrong?” he asked.

Sarah shouted through her tears. “You know what’s wrong,” she said. “I didn’t want to do that.”

“You’re fine,” he replied. “You’re with me.”

Sarah had a hard time processing what had happened to her. It happened so quickly and without warning. It was still her first month on campus. She had no idea who to call or where to go. She had thought she could trust Brian, and she was hesitant to tell anyone.

She blocked Brian from her phone and prayed she didn’t run into him in Olive or on campus.

“I didn’t want to call it rape,” Sarah said. “I think that’s part of the reason I didn’t say anything.”

The trauma of what had happened lingered within her. Every time she turned a corner in Olive, or an elevator door opened, she scanned for his face. She became increasingly panicked but tried telling herself what had happened was no big deal. Afterall, she still had the rest of the semester–and the rest of college–ahead of her.

“I was trying to justify something that’s not justifiable,” Sarah said. “For the sake of my mental health, for the sake of my mind space. My parents still don’t know.”

At the Homecoming Pep Rally, Brian briefly approached her. Her friend, Devon*, asked how she knew Brian. Devon warned her that Brian had raped his friend Abigail*. Sarah broke down and told Devon what happened. She was wracked with so much guilt she threw up.

“I realized I was raped, and I didn’t say anything about it,” Sarah said. “And because I didn’t say anything about it, it led to this happening to other girls.”

II.

Abigail, a sophomore, met Brian at a fraternity party in September. Since his night with Sarah, he had pledged Pi Kappa Alpha, “Pike” for short. Brian and Abigail had been drinking, but their interactions were only flirty. Neither of them was looking for anything serious, but they made great conversation partners.

After the party, the pair continued to hang out. They would chat in the dorms and watch movies together, but never had a single sexual interaction. They were just friends.

“It was really nice to talk about meaningful things,” Abigail said. “That’s what drew me into him. It wasn’t just ‘I wanna f–k and be done.’ He put thought and effort in, and he cared.”

Abigail trusted Brian. He made her feel comfortable talking about the most uncomfortable things, including a previous experience she had with sexual assault.

The night of a friend’s birthday in October, Abigail and Brian went to a house to party. From there, the celebration continued to at a bar in town. They both drank and had fun, but as the night wound down, a friend drove them back to Olive Hall. In Brian’s room, Abigail noticed two 24-packs of Bud Light.

Brian and his friend cracked open the cases, but Abigail declined the beer since she was already buzzed. The friends laughed and joked until 2 a.m. When only Brian and Abigail remained, he confessed his feelings for her and kissed her.

“He said, ‘I can’t date you until after initiation, but I wanna be with you. I wanna hang out with you. I really enjoy being around you,’” Abigail said. “I was like ‘Okay, I’m fine with waiting,’ because it wasn’t something I had expected.”

Abigail started to fall asleep after the late night full of fun, but she hadn’t paid attention to just how much Brian was drinking. She noticed the first case was completely empty and the second had a sizable chunk missing from it.

“I didn’t realize how f–ked up he was,” Abigail said. “I told him ‘No, I’m not doing anything with you tonight. I don’t want to do anything with you tonight. I’m tired. You’re f–ked up. I just want to go to bed.’”

By this point, it was 3 a.m. Abigail was exhausted, still tipsy and opposed to walking back to Appleby in the cold and dark. She thought about calling her friends, but knew they were drunk too or fast asleep after a long night of partying. She decided it was safer just to stay put.

They kissed again, but Brian wanted their interaction to go further.

“Brian, I’m not doing anything with you tonight,” Abigail said. “I don’t want to do anything with you. You’re f–ked up. Please stop. Let’s just go to bed.”

But in the next instant, she was undressed, and Brian was inside of her.

“I just continued because he’s 6’4”,” Abigail said. “I’m 5’2”. He’s in ROTC. I’m not trying to fight that.”

Abigail stayed silent the entire time. She figured the faster it was over with, the better. When Brian finally stopped, she started bawling. Brian nervously handed over her clothes, and Abigail ran into the bathroom. He pleaded with her to stay.

“I’m so sorry. I f–ked up,” Brian said. “I really like you, and I f–ked all this up,”

“Yeah,” Abigail said. “You kinda just assaulted me.”

“Please don’t tell anyone,” Brian said. “Please don’t say anything. You know I would never do that to you, I’m just f–ked up. I’m not here right now. I’m just drunk.”

“Drunk is not an excuse,” Abigail said.

“I’m sorry,” Brian said. “I know you’ve been through so much, and I know this has happened to you before.”

“No,” Abigail said. “I told you repeatedly that I didn’t want to do anything. I’ve been drunk before too, and I know not to touch people when it’s not okay.”

The conversation continued in circles until Abigail finally went to bed around 5 a.m. As soon as the sun rose, she walked back to Appleby.

“I struggled for so long with what to call it because I felt like it wasn’t assault because I didn’t leave right when it happened,” Abigail said. “It hurts because he proclaims to be religious and claims that he’s a man of God.”

Abigail struggled with what to do, and she had convinced herself it was her fault for not fighting more aggressively. She assured herself it wasn’t rape since she had known him. She told a few friends about what happened including Devon who connected her to Sarah. The two bonded over how similar their experiences were: How charming Brian seemed early on, his sudden excessive drinking, the quick forcefulness by which he overtook them.

In November, Abigail saw Brian dancing with one of her sorority sisters at an event. Her sister Emily*, who she didn’t know well, rolled her eyes.

“Who let that rapist into our party?” Emily said.

“What did you just say?” Abigail said.

“I said, ‘Who let that rapist into our party?’” Emily repeated.

“How did you know that happened to me?” Abigail asked.

“Happened to you?” she said. “Brian raped me.”

III.

Emily, a freshman, matched with Brian on Tinder in November. When she found out he lived in Olive, her dorm also, she asked him to come hang out in her room. They talked for a long time before starting a movie.

When the movie started, he lay down on the couch in her room. Emily didn’t want to seem uptight, so she lay down next to him.

The assault happened so quickly Emily didn’t have time to process what was happening.

“When you’re in that situation you don’t know what to do,” Emily said. “The guy that assaulted me is 6’4”, and I’m 5’7”. He’s so much taller than me and so much stronger than me. What am I supposed to do?”

At first, Emily thought it was just a hook-up gone wrong. But after she described the incident to a friend, she knew she had been raped.

“I told Brian beforehand I didn’t want to have sex,” Emily said. “He looked me in the eyes afterwards and said, ‘So much for not having sex.’ He knew that I didn’t want to have sex with him. He knew that I did not want any of it.”

Her friends encouraged her to report the incident, and she stayed in their room – too nervous to be in her single dorm alone after what happened. The Olive Resident Advisor called the UNA Police. The officers ran Emily through a list of options: she could opt for a restraining order, no contact order or press charges.

“At first, I didn’t want to do anything,” Emily said. “But when I found out one of my [sorority] sisters had also been assaulted by him, it sent me into a rage.”

Emily pressed charges and reported the incident to Title IX, Pike and ROTC.

“Since the assault didn’t happen at the Pike House or after a Pike Party, Pike can’t do anything,” Emily said. “ROTC can’t do anything because he’s not on contract. He’s just taking the classes, but he’s bought the uniform and acts like he’s in ROTC.”

At the Lauderdale County Court, Emily had a similarly discouraging experience.

“They treated me like a child at the courts,” Emily said. “I know the way our system is set up: you need to be proven guilty without a reasonable doubt. If there is doubt, you can’t be proven guilty. And there was doubt in my case.”

When Emily heard from Title IX via email, she was unsure of what exactly to do as her world collapsed around her. The office sent her a 39-page document detailing the “UNA Processes and procedures related to Sexual Misconduct Policy.” Though the office let Emily know the Olive RA filed a report on her behalf, they never met in person. In January, they closed her case.

“[UNA PD] offered to move me [from Olive],” Emily said. “I don’t feel like as sexual assault victims we should have to uproot our lives. He should be the one who has to uproot his life, not me.”

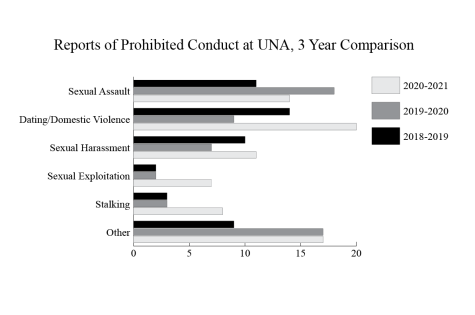

According to the 2020-2021 Annual Title IX report, the office sent of 500 emails, letters and phone calls regarding pending or potential Title IX investigations. They issued 17 no contact orders. There were 14 reports of sexual assault, 20 reports of dating/domestic violence, 11 reports of sexual harassment, 7 reports of sexual exploitation, 8 reports of stalking and 17 reports labeled “other.”

“I still have to run the risk of seeing Brian all the time [in Olive],” Emily said. “Thankfully, I haven’t gotten in the elevator with him yet.”

The 2021 UNA Annual Security & Fire Safety Report shows statistics of reports made to the police. In 2020, only 4 rapes, 2 incidents of dating violence and 2 incidents of domestic violence were reported. But sexual assaults across the country are significantly under reported. According to RAINN, the nation’s largest anti-sexual violence organization, only 31% of sexual assaults are reported to the police.

“I tried to convince myself it wasn’t rape,” Emily said. “But my friends keep telling me I need to let myself acknowledge that it was. It feels like I’m just another number.”

IV.

Anyone on campus can file a report with Title IX if they know of a sexual assault. The complainant–the word Title IX uses instead of “victim” or “survivor”–does not have to be the reporter. In the 2020-2021 school year, most reports came from faculty and staff.

“A report in and of itself does not necessarily trigger an investigation,” said UNA Title IX Coordinator Kayleigh Baker. “In the cases where we have that flexibility, we want to give the ability to the complainant to decide whether they move forward with an investigation or not.”

If Title IX receives a report with the complainants’ name, they send a letter via email explaining what Title IX can do for them. The report includes information with resources and options for moving forward in the Title IX process.

“Under Title IX, we cannot require anyone to come in and meet with us,” Baker said. “The complainants do not have to respond to that email if they don’t want to.”

If a complainant chooses not to respond, Title IX reaches out once again before closing the case.

“One option that everybody always has is they can do nothing,” Baker said. “That is a perfectly valid option, and it is not my job or anyone else in our office’s job to try to convince them that they need to do something.”

Additionally, Title IX investigations only explore violations of the Student Code of Conduct. If students want to press charges, they must go through a separate process with the police department.

Overall, the Title IX process is dense and complicated by its bureaucracy, legal procedure and bound to the federal regulations of the moment. The Department of Education implemented new Title IX regulations in August 2020. Controversially, it introduced a live hearing at the end of the formal grievance process. Debates swelled at the national and local levels about if this would deter students from reporting. However, the Biden Administration is likely to unveil changes to Title IX any day now.

According to a study from Know Your Title IX, an advocacy group working to end sexual violence on campuses, 70% of survivors who reported sexual assault to their universities experienced negative effects on their safety and privacy. And because Title IX is tied to strictly to its process, victims of sexual assault often struggle with the choice to report misconduct or not.

“I had a friend at Belmont who was talked out of going to Title IX by Title IX,” Abigail said. “That’s not how this should be.”

Instead of following the formal approach, sometimes survivors seek alternative means of justice–like Emily, who doesn’t expect her assailant to be expelled from campus.

“I wish that he could just be out of his fraternity,” Emily said. “Out of ROTC and out of the dorms.”

Women in sororities are 74% more likely to experience rape in college than non-affiliated women according to research from the Journal of Student Affairs Research and Practice.

Fraternity men are also disproportionately more likely to commit sexual assault than their independent peers.

Will Crabb, Pike’s Theta Alpha chapter president, declined multiple attempts to interview due to scheduling conflicts. He offered Howard Copper, the chapter’s external vice president, to answer any questions.

“For me, [sexual assault] is a growing issue on campus that should not be taken lightly,” Howard Cooper said. “[Pike] has a zero-tolerance policy, and we strive to create a culture of accountability.”

Yet, Cooper claims that during his time in Pike leadership and prior to his interview, no one has reported a brother’s sexual assault to their chapter.

“We’re going to be accountable because we will not stand for it,” Cooper said. “Administration puts a lot of the responsibility for women to prevent sexual assault and they need to do more to educate guys from doing the bare minimum and not assaulting people.”

UNA requires students and employees to complete sexual assault prevention training through Get Inclusive – Voices for Change. They assess the success of this training through the annual campus climate survey.

“Pike already has a bad reputation,” Emily said. “Having someone with three sexual assault cases against them…that’s just not helping them.”

At the time Title IX inundates complainants with resources, survivors may not even have come to terms with what happened to them, and everyone responds differently. The pain of coping with an incident of sexual assault can often be easier than the pain of being let down by others.

“I shove it down,” Abigail said. “[Assaults] should all be reported, but the ratio of them believing women over men is slim, and I can’t handle that.”

Institutional barriers aren’t the only things dissuading survivors from coming forward. Sarah never told her parents in fear they wouldn’t believe her.

“I love my mom,” Sarah said. “But she told me if I ever got raped it would be my own fault. And it happened.”

Survivors also experience a range of emotions day to day.

“First, I had a meltdown, and I just broke,” Emily said. “But now if I could, I would beat his ass.”

While some women choose to keep their stories to themselves now, they may grow ready to talk with time. Sarah initially feared opening up to anyone, then claimed that speaking up gave her an opportunity to take her power back.

“We have more than three women [who Brian assaulted],” Sarah said. “We have three women who have spoken up, but that means there has to be a lot of women who are staying silent.”

This investigation is ongoing. If you have more information about sexual misconduct on campus and would like to talk to The Flor-Ala, email Audrey Johnson at [email protected].

![Caleb Crumpton [COURTESY OF UNA SGA]](https://theflorala.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/caleb-crumpton-courtesy-of-SGA-425x600.jpg)

rachel • Apr 15, 2022 at 7:45 pm

Since before I even knew what the word rape meant, it’s been the subject of every single nightmare. I’ve heard so many stories similar from fellow students while I was at UNA. So many even reported to the campus police like they were advised to do. But instead they were silenced. With or without proof, it didn’t matter. None of these young men were asked even a single question and none of these young women ever got justice. I understand some of the offenders are in fraternities and I’ve heard stories about members in each fraternity and each group UNA has it feels like. What I don’t understand is why no one is dragging the school? Why aren’t we asking the school more questions? UNA (along with so many other schools across the country) brushing women’s stories under the rug encourages this scary behavior by letting the bad guys know they can get away with whatever they want if it means UNA gets to save face.

Brian • Jul 7, 2024 at 9:23 pm

Because this story is garbage. It’s FAKE and there was no Rape. This is all ridiculous -for one the girls were naked and having sex for the weekend and all in a manner of minutes. “Brian” should sue for defamation!! This is all lies on these girls trying to say they were raped after working out their stories together. All laughable and sad that they had to try and ruin a young man’s life. All of these people are guilty of having SEX – simple as that.

Drunk Burma • Apr 14, 2022 at 8:14 pm

A piece of constructive criticism: the decision to include fictional names instead of some other placeholder choice for a withheld identity in this article is a bit wonky, and I would imagine–given that the identities of those involved are unknown–potentially discomforting for anyone on campus who shares the fictional names. This decision also depends on the idea that your readers will all be diligent enough to pay attention to the brief note that the names are merely placeholders. I do understand the desire not to refer to these people as “Victim 1” & “Victim 2” or something so dehumanizing as that, but even so, this choice seems a mistake.

Miranda Nabors • Apr 14, 2022 at 1:46 pm

This is empowering to women to speak out. This is awful for anyone to experience. My thoughts and prayers go out to these girls.

Christina Zarazua • Apr 14, 2022 at 8:41 am

I’d like to point something out that is dense on Title IX’s part. Students are required to meet with Title IX for illegal activity on campus such as drinking and drugs. How come the crime of underage drinking and substance use is required to be seen yet the crime of assaulting a fellow classmate, accused by not one or two but three women, is not? It is dense to throw the “they don’t have to come in if they don’t want to” card. UNA Title IX holds the responsibility to reach out to their students in these possible situations, whether it happened or not. This is not the time to sit back and see; it shows an immense amount of ignorance on Title IX’s part, and after the SGA incident, anti-women/gay protests on campus, and hundreds of reported sexual assault cases since 2021, I am certain to say I am ashamed that I go to UNA.

Brian • Jul 7, 2024 at 9:29 pm

This was never sexual assault…it is called premarital sex at best. This story if true makes it seem like these girls are vindictive for some reason and it’s not really rape. A girl sleeps with Brian for a couple days and several times and then calls rape months to a year later…I call bullcrap!