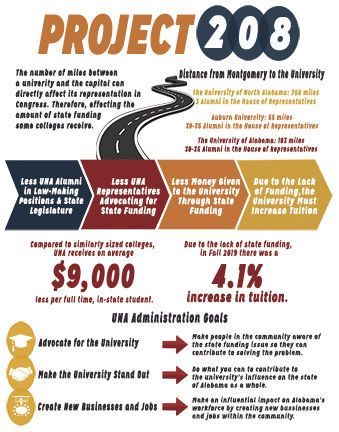

The long road to Montgomery: UNA’s fight for fair share of state funding

January 16, 2020

There’s a long, two-hundred-and-eight-mile road that separates the University of North Alabama from Montgomery.

Here, asphalt and concrete carve the ground, creating a path through the center of an old state filled with turmoil and triumph. In the northwest corner, far away from the seat of power, the oldest four-year public university in Alabama is plagued with a $26 million annual deficit from its own state capitol.

Out of the fourteen public universities in Alabama, UNA has historically placed last or close to it in terms of state appropriated funding. Data researched by the university shows that when compared to other in-state comparable sized universities, UNA is appropriated an average of $10 million less annually despite the recent increase in the university’s enrollment.

This deficit is not new. The 13thpresident of Florence Normal School (one of UNA’s original names), Dr. Henry J. Willingham, who served at the helm from 1913-1937, faced the struggles the university was having with its relationship with Montgomery,

“The institution has done its best with the small amount of money appropriated for it. Its income…is equal to that of the lowest fourth of the institutions.”

This same struggle, which has been present for over a hundred years, is the main focus of UNA’s current president Dr. Kenneth Kitts. When taking office in 2015, Kitts made it clear that this disparity from the state would need to be eliminated for the future of the university.

Shortly after taking office, Kitts was overwhelmed with the so-called “loose talk” that his university wasn’t getting its fair share from Montgomery. He quickly became aware that this was a crucial issue, one that needed to be defined before any attempt to accurately speak to it could be made.

“The first thing you have to do before you can address a problem is you have to define the problem,” Kitts explained. “I can’t make decisions based on loose talk. [I told them] we’ve got to get some very good, precise numbers on this.”

Working with the university’s institutional research office, Kitts gathered data and comparisons. He needed to see the exact affect Montgomery was having on UNA. Kitts says what was found was overwhelming,

“When we started analyzing… crunching the numbers, getting bar graphs and pie charts; when I first saw it [all], my jaw hit the ground,” Kitts said. “It showed with absolute clarity that we’re not just a little bit behind, we’re dead last.”

Kitts went on to task the university with Project 208, a project backed by the data researched and focused ultimately on funding equity for UNA. Kitts says these numbers are still shocking to see, as well as still having a tremendous impact,

“We’re getting $10 million less each year, every year,” Kitts said. “It hasn’t changed much and over a decade that means we’re getting $100 million less… it’s absolutely staggering.”

This funding deficit becomes even larger when looked at on a per-student basis.

“You know, Auburn gets a lot more [money] than we do [and] they should; they’re a larger school,” Kitts said. “But on a ‘per-student basis’, [it] becomes a much more interesting comparison.”

In Fall 2016, UNA received $5,043.47 per in-state student. This was 45.8% below the state median. This gap translates into UNA receiving the least amount from the state per in-state student when compared with all other fourteen Alabama public institutions.

UNA is dead last.

When compared with five similar sized Alabama institutions, UNA received an average of $9,000 less per full-time, in-state student.

“Everyone’s been making do,” says Evan Thornton, the Chief Financial Officer of UNA and head of UNA’s Human Resources. “We need people to get mad about it.”

Thornton has been ahead of the university’s budget since 2015. Every year, the budget committee meets and initiatives are turned in to create the budget. Those initiatives are reviewed and ranked, finally going to Dr. Kenneth Kitts for definitive approval.

Thornton stares at these numbers every day, he knows the weight they carry and the potential each dollar has to secure a better future for the university. That’s his job.

In 2018, $795,000 worth of on-sight staff or faculty positions were purposely unfilled by the university because of the lack of state funding. At least seventeen significant absences in important positions across multiple areas, everything from professors to groundskeepers.

By contrast, the two closest Alabama universities comparable in full-time student enrollment (FTE) size to UNA, one 600 FTE smaller and one 700 FTE larger, both employee 100-200 more full-time faculty and staff.

The effect of these numbers is not just on paper, they are translated into the university’s student body. In Fall 2019, tuition at UNA was increased by 4.1 percent out of the direct impact of the lack of funding.

“We work very, very hard… to make sure that [our students] don’t see the impact anywhere else on campus,” Kitts said. “We try not to skimp on faculty lines or the beauty of the campus, [our students] have a right to that.”

There’s a very basic relationship between state funding and tuition prices. When funding is up, tuition goes down and vice versa. This simplicity is both a positive and a negative. Its positivity is in the basic understanding of how it works and its relative ease of application. The negativity is found when two and two don’t equal four and money is not found where it should be.

In UNA terms, this means tuition must continue to rise until a breakthrough from the funding deficit is made.

The math works like this: UNA’s budget for 2019 is $125 million, they receive $32 million from the state. Taking the $125 million, subtracting the $32 million from the state, equates to $93 million that is needed to run the university.

“Again, if you started with $50 million… or $60 million from the state,” Kitts said. “[The question] would [instead] be, ‘how do we make up $70 million or $80 million?’ It’s much easier.”

If the numbers are all there and the inequality is obvious, where’s the solution? The university quickly realized that presenting numbers alone wasn’t going to solve anything. In a sense, they were treating the symptoms without identifying the cause.

The easiest contributor of the issue to pinpoint is the distance between the university and the governing body that upholds it. Two-hundred and eight miles from Montgomery; that’s a long way.

If one was to draw a circle with a one hundred-mile radius around the university, not only would it fail to reach halfway to Montgomery, nearly 2/3rds of that circle would be in two completely different states, Tennessee and Mississippi.

This ‘circle of influence’ is more important than one might think.

“When decisions are made, we’re starting the discussion in Montgomery with half the number of representatives and senators from our area,” Kitts said. “If you go north from our area, you’re in Tennessee, if you go west, you’re in Mississippi.”

This circle also brings up an important political factor that has a drastic effect on UNA. There is a total of 140 lawmakers in Montgomery, 35 Senators and 105 in the Alabama

House of Representatives.

Of those 105 representatives, UNA only has three alumni seated. Compared to the two biggest schools in Alabama, The University of Alabama and Auburn University, 30-35 alumni from each school are seated in the Alabama House.

Doing the simple math, it’s clear of those two schools, half of all Alabama representatives have ties to either UA or AU.

“You have a lot of senators and representatives who say, ‘Yeah, that’s my school, I’m going make sure they get fairness,” Kitts explained. “That’s a political consequence of not only being far away [from Montgomery] but being in the corner of the state. No other school really has to deal with [that].”

This ‘political consequence’ is furthered by the way funding to public universities works in Alabama.

In many ways, Alabama is behind. Like most of her history, Alabama has failed to quickly change the operations of an outdated system.

In most states, funding for higher education is a function of enrollment or solely based on the university’s performance; how well they do in areas such as graduation rate on a per year basis.

“I came to Alabama and I found out that funding here is not tied to anything at all,” Kitts said. “It’s arbitrary, which means it’s political.”

Because of this political based funding system, representation in Montgomery is everything. Without a voice, there is little say in how much money one school gets over another.

Of the three UNA alumni seated as Alabama legislators, Rep. Jamie Kiel is the newest.

Elected in 2018, Kiel graduated from UNA with a degree in Management and Marketing. Starting his business, Kiel Equipment, he went on to run for the Alabama House. He is now the first voice from UNA to have a seat on the House Ways and Means Education Committee and is very much involved in the funding issue present at UNA.

“I talk to Dr. Kitts pretty often,” Kiel said. “We talk about needs, even during the session when we’re working on the budget, I talk with [UNA] about the needs that they have. It’s just hard to get ahead, because [UNA is] so far behind.”

Just five years ago, UNA had no alumni representation in Montgomery. Kiel says this makes a huge difference.

“We’ve just been underrepresented for all these years,” Kiel said. “[It’s] definitely a factor, we just haven’t had a voice in Montgomery.”

With the recent additions of Keil and the two other UNA alumni to the Alabama legislator, the word is beginning to spread through their shared voice. Before, when Montgomery was made aware of the numbers and disparity occurring at UNA, they were shocked,

“Occasionally…the state will come in and they’ll say, ‘Okay, okay, good point. So, this year we’ll give you 10% and this school that’s better funded only gets 8%’,” Kitts said. “The problem is 10% of this number and 8% of this number; they’re still getting more dollars. They think they’re helping us.”

Last year, Kitts began inviting influential Alabama lawmakers to his campus. Seated on the presidential golf cart, they make the rounds of the institution. Kitts highlights key visual areas that truly show the problem at hand.

“[I show them] the swimming pool and Flowers [Hall] that we had to close last year because we don’t have enough money,” Kitts said. “I take them to the music building and they’re literally teaching classes in a building that has leaks…there’s a puddle in the room.”

Kitts says that highlighting and identifying the problem, showing it in a way that ‘busy people’ can understand has been the main focus of Project 208 for the past couple of years. Now that focus is shifting to a ‘what are we going to do about it?’ mentality.

Rep. Jamie Kiel believes this mentality is here to stay, but a major problem is the lack of unity between the community and alumni.

“We could make noise and be heard,” Kiel said. “But I think generally they have not been rallied, they haven’t been unified and haven’t been made aware that there is a funding discrepancy.”

The lack of knowledge of the overall importance of this issue between the community and alumni is a key factor affecting the push the for change.

In a recent AL.com article, north Alabama is featured in a workforce analysis. Alabama’s unemployment rate is at 2.8 percent as of 2019, this number drops further in the north of the state.

With the major influx of new businesses and jobs to the area, a job-market crash is looming if north Alabama can’t find a way to fill these new positions.

Kiel says this threat is a real opportunity for schools like UNA to receive better funding.

“Those schools that can make a case [to Montgomery] that they can provide [workforce development] will stand to make budget gains,” Kiel said.

In other words, if UNA can have an influential impact to north Alabama’s much needed workforce, the state would be more inclined to send the university more money.

In a state where funding and influence are based so heavily upon each other, the University of North Alabama’s influence and impact on the state as a whole is critical to the university’s future.

“It’s fairness,” Kitts said. “That’s [the] reason we’re fighting as hard as we are, it’s just not fair to our students.”