FAM Series: “Scottsboro Unmasked: Decatur’s Story”

LOCAL FEATURE

October 7, 2021

Pope’s Tavern Museum hosted its first presentation in the Florence Arts and Museum (FAM) Speaker Series on Sept. 26 in the Florence Indian Mound.

The series originally began as Pope’s Tavern’s Speaker Series in 2019, but two years later, they decided to revamp the presentation and move it in a bigger space. The FAM series will feature a different topic and speaker on the second-to-last week of every month until April.

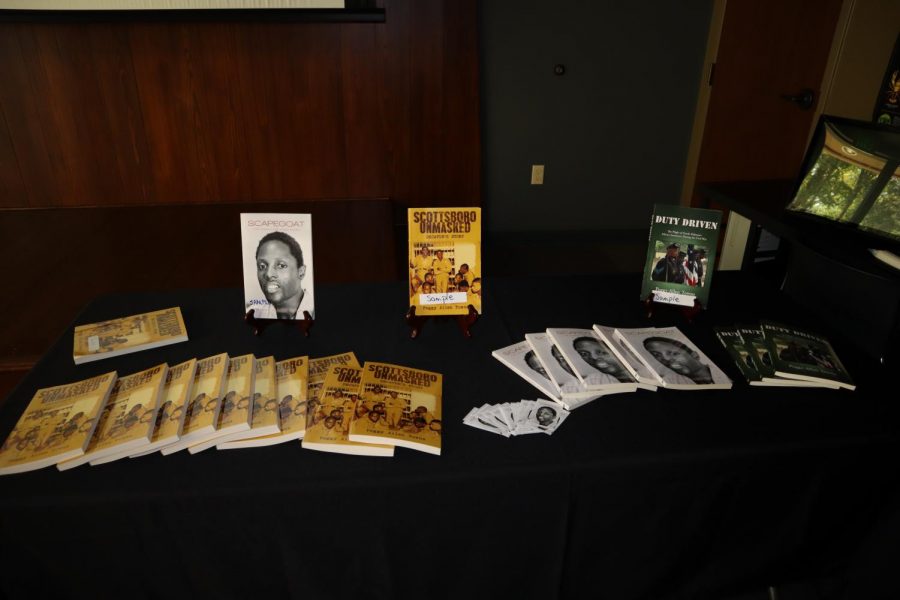

Kicking off this series was Peggy Allen Towns, an author and historian of African-American history. Towns spoke on her second book, which was published in 2018, “Scottsboro Unmasked: Decatur’s Story.”

“Scottsboro Unmasked: Decatur’s Story” covers the incident of the Scottsboro Boys. The Scottsboro Boys – Charlie Weems, Ozie Powell, Eugene Williams, Andy Wright, Clarence Norris, Haywood Patterson, Olen Montgomery, Willie Roberson and Roy Wright – were African-American youth who were falsely accused of raping two white girls in 1931.

Inspiration for this book came from being on a committee for Big Read, an initiative designed to restore reading to the center of American culture.

“In 2009, I was asked to be a part of [this] program where the community read To Kill a Mockingbird,” Towns said. “I was asked to do a walking tour, because many people believed the [Scottsboro Boys] trials inspired Harper Lee to write. I do genealogy, so, the sleuth in me had to do some investigating.”

Towns discovered that many people did not know that all but the first trial took place in Decatur, her native city, or that an African American had not been seen on a jury since the Reconstruction era.

“I had said when I retire, I [was] going to write a book about the Scottsboro Boys,” said Towns.

Towns retired in 2011. While researching the Scottsboro Boys, Towns also dove into her own family history, where she discovered that a relative had served with the 110th United States Colored Infantry. She published her first book, “Duty Driven: The Plight of North Alabama’s African Americans during the Civil War” on her findings in 2012.

“I [like to] tell people that I tell the other side of the story,” Towns said. “When you pick up a history book here in the state, nine times out of ten, you’re not going to read about U.S. CT soldiers. You’re not going to read about the Scottsboro Boys case, where two landmark Supreme Court decisions came out of that trial.”

“Scottsboro Unmasked: Decatur’s Story” dives further into the trial, presenting readers with resources. Towns provides archives of documents and photos and holds exclusive interviews with relatives of those involved in the original cases.

By doing this, Towns adds a new dimension to the Scottsboro Boys story by resurrecting the experiences and of people in the community.

Towns said that there are “thousands” of books written about the Scottsboro trial, but there are not any that tell Decatur’s story.

“It’s not just about blacks, but whites as well,” Towns said. “In my books, my goal is to inspire and encourage, but also to show that these things happen but to show the courage, the bravery that people had as well.”

Throughout her presentation, Towns points out a lion icon she put beside quotes she felt took courage to say during the Scottsboro Boys trial. For example, “C.S.” Finley testified that he had never seen a black man in the jury and said he knew “a lot of them [whites] are not competent to be on the jury.”

“Scottsboro Unmasked: Decatur’s Story” goes in depth of the nine boys’ cases, of their retrial after retrial, painting a picture of the color line and the bravery of people who took a stand for justice.

Finally, on April 22, 2013, 83 years after the boys were convicted of a “crime that never happened,” the Scottsboro Boys were exonerated by former Alabama Governor, Robert Bentley. On this day, Bentley stated that the boys had “finally received justice.”

Towns concluded her book with a statement.

“For decades, people of color have suffered and still experience unfairness in the criminal justice system,” said Towns in her book. “While America has experienced many changes, from slavery to Jim Crowe laws, from Civil Rights movement to present, the wheels of justice move slow when it comes to discrimination in this area.”

Towns uses Kharon Davis as an example of the racial profiling, police brutality and “senseless murders under the ‘stand your ground’ laws.” Davis, a black man, who as of late 2017, had been in an Alabama jail for a decade without bail or a trial.

English Associate Professor Katie Owens-Murphy, who attended Town’s presentation, can recognize the inequalities of the criminal-legal system as well.

“We can still see these racial disparities in the Alabama prison system,” Owens-Murphy said. “26.8% of people living in Alabama are Black; 54% of people who are incarcerated in Alabama are Black. This means that Black people are grossly over-represented in our criminal-legal system, and racial disparities exist from initial contact with law enforcement to criminal sentencing.”

Owens-Murphy said that most people serving life without parole sentences are also black.

“One way to address these inequalities is to look at other models of justice, harm prevention and harm reduction,” Owens-Murphy said. “Several colleagues and I are building a certificate program in Restorative Justice through the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program here at UNA.”

According to una.edu, the Inside-Out Exchange Program is based on the belief that society is strengthened when higher education is made widely accessible and allows participants to encounter each other as equals, often across profound social barriers.

Owens-Murphy said the program does not focus on punishing offenders, but focuses on addressing and repairing harm and rebuilding community trust.

“The Scottsboro Boys trial began with a simple fight on a train,” Owens-Murphy said. “Imagine what a different outcome there might have been had we applied a restorative rather than punitive lens to that situation.”