The complexity of Black athleticism

Black Athletiscism

February 28, 2022

Organized sports have played an integral role in Black culture for centuries. They are often regarded as one of the first facets of modern American culture to normalize racial equality. Since the mid-1900s, the numerous aspects of African American ethnology that arose from the world of sports, namely football and basketball, have come to be celebrated by the masses.

The popularity of the National Basketball League’s signature sneakers like Nike’s Air Jordans has been steadily skyrocketing for over forty years. The shoes’ continuously-rising number of admirers is due almost completely to the influence of traditionally Black stylistic proclivities on regulated sports, alongside regulated sports’ respective influence on customary American habit. Substantially, the most influential athletes throughout the history of formal American sports have been Black. African Americans account for 41 percent of the rosters in the five major American sports leagues. Significantly, they constitute the majority of athletes in both the National Football League, or the NFL, and the National Basketball Association. Recently, newly unemployed head coach Brian Flores filed a lawsuit against the NFL on grounds associated with race-based discrimination. In the aftermath of his legal advancements, the New York Times published an article informing the public that the NFL is composed of 70 percent African American players. Similarly, in 2020, at a critical point in the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement, popular online sports forum Interbasket analyzed NBA statistics to find that at the time, just over 81 percent of its players were Black.

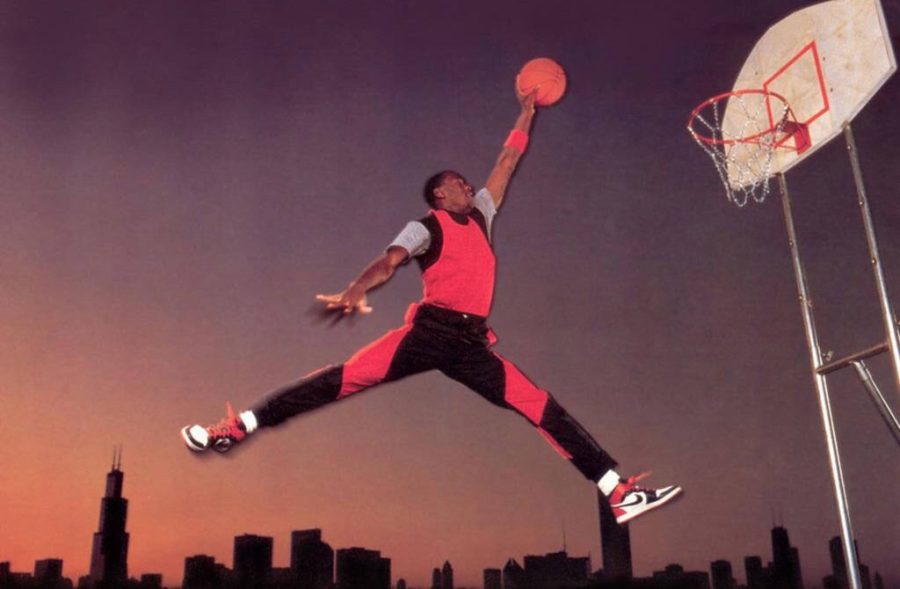

Michael Jordan, the force behind the above-mentioned sneakers, is thought throughout the nation to be, as the NBA’s website puts it, “the greatest basketball player of all time.” It is widely accepted that he has had an immeasurable impact on American civilization.

Black football star Cam Newton, who belongs to the NFL’s Carolina Panthers, has received an abundance of notable awards for the duration of his athletic career thus far. He is lauded in Alabama particularly, as a large portion of his years gaining fame were spent playing for Auburn University, the state’s second-largest major college, behind the University of Alabama.

It appears as though the full scope of Black athleticism is realized by the representative United States citizen, regardless of their race. However, the part of African Americans in sports is a troubled one, and Americans often turn a blind eye to the many negative implications of their dominance on fields and courts across the country.

When a casual football or basketball fan looks at the disproportionate ratio of Black to white Americans in the NFL and NBA, it would be easy for her to come to the conclusion that Black Americans have some sort of natural knack for athleticism, but this assumption, upon further examination, would prove erroneous, not to mention ignorant.

On Friday, February 11, president of the newly-formed University of North Alabama’s Black Lioness Alliance and strikingly involved political science major Lele Emons was questioned as to her views on the topic at hand. On the habit of the American populace to equate having traditionally Black features with having a high chance of achieving victory on the playing fields, she says, “When it comes to a lot of sports, Black athletes dominate. In America, the stereotype is that we go into either music or sports. You know, nobody wants to highlight our scientific achievements. Like, you never hear about Black doctors. They prefer us as athletes.”

African Americans’ supposed sports-centered superiority is a myth. Historically speaking, Black athletes have been trailblazers and changemakers, tearing down racial barriers and exhibiting physical prowess in the sports industry. Today, society does not shy away from showing its appreciation for prominent Black competitors working under the purview of regimented sports. These truths do not change the reality of the matter – American sporting programs, primarily those affiliated with football and basketball, are predominantly excelled at by Black men and women because Black children are systematically taught by the American education system that collectively, their sole chance of success lies in their ability to be either exceedingly physically imposing or unfalteringly entertaining.

“It’s easy for Americans to profit off of Black culture,” Emons asserts, “but they don’t want to treat us fairly, and that’s a problem.”

The verifiable failure to properly equip Black students with sufficient academic self-confidence on behalf of mainstream Usonian pedagogy was studied in 1971 by Dr. Harry Edwards, as sports writer Reagan Griffin Jr. brought to light in a recent article for the Guardian. Edwards penned a piece titled “The Sources of the Black Athlete’s Superiority”, in which he wrote, “whites, being the dominant group in the society [of the U.S.], have access to all means toward achieving desirable valuables defined by society. Blacks on the other hand are channeled into one or two endeavors open to them – sports, and to a lesser degree – entertainment.”

In addition to their tendency to be viewed by young and ambitious African Americans as a meal ticket, football and basketball are

relatively affordable athletic pursuits. Their financial feasibility, in comparison to other, more equipment-heavy sports, say baseball and tennis, is appealing to juveniles from low-income households. Taking note of the current state of the wealth disparity between Black and white families in North America, it should not come as a shock that Black children far outnumber their white counterparts in regional

football and basketball groups, nor should it be surprising that the opposite rings true for white kids enrolled inexpensive golf clubs and soccer camps. As indicated by the Federal Reserve System in 2019, the standard white family in America possesses eight times the wealth of its Black parallel.

“In poorer, predominantly Black areas,” says Emons, “a career in sports is the only option kids think they have. I blame that to cities and school systems. What you’ve got to think about is that a lot of Black athletes come from nothing. We can’t depend on systems that are made to work against us.” Americans do themselves a disservice when they neglect to address the fact that Black football and basketball players work unfathomably hard for their sportsmanly successes and reap from them devastatingly few benefits.

In 2020, the business of selling basketball sneakers saw a yield of $70 billion; little of those profits went into the pockets of Black venders, nor did they contribute to the earnings of their individual establishments. Famous Black athletes like Michael Jordan and Cam Newton are praised for their kinesthetic know-how, yet they’re singular intellectual idiosyncrasies are ignored. The average Alabamian may appreciatively familiarize herself with statistics spanning the totality of Cam Newton’s professional career, but she is unlikely to hold him in regard as someone capable of critical thinking or introspection, rather than as a mere medium through which her preferred football team can win matches.

U.S. denizens have impermissible but understandably-conceived misconceptions about African American athletes and their physical attributes, remorselessly making uninformed connections between their game time wins and their genetic makeups. If their country wants the right to boast its oft-mentioned but scantily satisfied status as a multicultural utopia, its white citizens must rid themselves of their preconceived notions about race. In their self-reflection, they need to cultivate among themselves a better understanding of the racially biased structures that facilitate the opportunities they are granted.

![Caleb Crumpton [COURTESY OF UNA SGA]](https://theflorala.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/caleb-crumpton-courtesy-of-SGA-425x600.jpg)